Has surf culture outgrown competitive surfing?

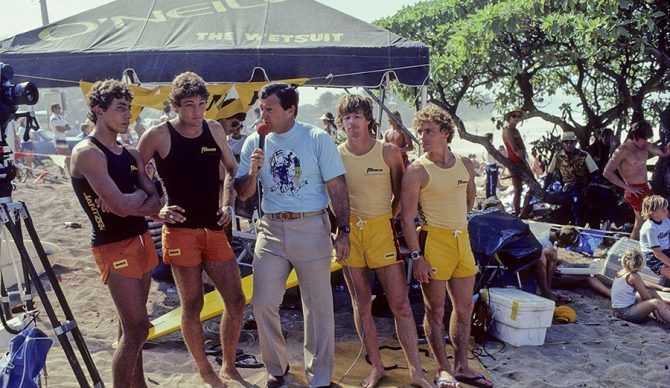

A scene that, after all these years, is not so different from the one below. Photo: Sean Rowland//WSL

I was never really a professional surfing competitor. This means that an honest personal assessment would place me far from a serious competitor, but rather as an enthusiastic member of the C+ team.

I surfed my first international pro surfer event in 1979 and I can’t say I’ve ever walked through any doors. Oh sure, sometimes I managed to cross out a few decent results, like the 1980 Malibu Pro quarter-final, where I was driven to the brink of tears by 1976 world champion Peter Townend who, brutally enforcing the rule of archaic interference, prevented me from catching more than one wave. And the Bells Beach Quiksilver Trials in 1983, when, like an uninvited wedding accident, I snuck into the final, finishing fourth behind surfing stars Gary Timperley, Mark Warren and Col Smith.

Today, however, I report my participation in the early days of the modern professional circuit, as well as the following decades covering the professional competitive scene in the role of surf magazine editor, simply to establish my qualification by making the following statement: No organization or sanctioning body has ever showcased professional surfing better than the World Surf League.

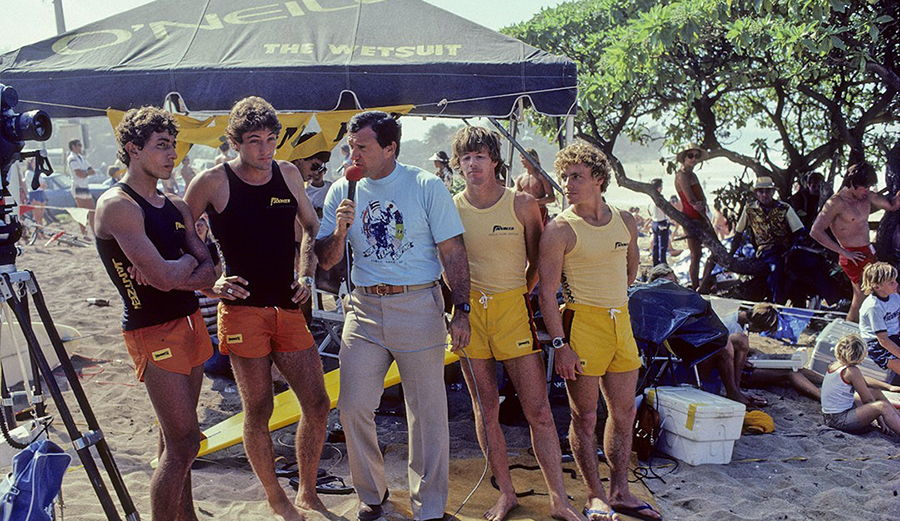

Beach interviews might have been more robust back then, but the end result is now similar to the old days. Photo: Jeff Divine

Consider what the WSL has brought to pro surfing fans, season after season since its inception in 2015: An international men’s and women’s circuit and a completely self-contained ranking system, completely divorced from any outside commercial interest. Prime locations, especially judging by the 2022 itinerary: Pipeline, Sunset Beach, Peniche, Bells Beach, Margaret River, G-Land, Punta Roca, J-Bay, Teahupo’o and Lower Trestles. With the exception of the Oi Rio Pro, not a sloppy beachbreak among the bunch; no eight-inch Chiba, Japan, or Sunday afternoon high-tide finale at Huntington Beach, like in the old days. And if the pros find riding an artificial wave of the kind that 99.9% of all other surfers in the world can only dream about is boring, then it’s their fault, not the WSL’s. Add, for good effect, excellent streaming coverage, capturing all the action from multiple camera angles, including drone and water photography, instant replays, as well as full event and heat-by-heat replays , competitor profiles and arcane stats and data.

Ok, the WSL commentary team, targets of the most ruthless critics, fully deserve their derisive nickname of “wall of positive noise”, but what are the pundits nostalgic for? The good old days? Like that time in the early 1980s, where at the Bells Beach contest, the event’s sponsors put one of their pros in the announcer’s booth for each of his teammate’s heats, where he called which wave in a set take? Anyway, what to expect when the men and women at the WSL announcer booth are, in fact, tour employees. Can you imagine what professional football commentary would look like if the NFL, not the networks, provided the commentators for every broadcast? Now this would be boring.

No, taking all of this into account, and viewed objectively, it’s hard to pinpoint what the WSL is doing wrong. Yet it often seems like the tour’s critics far outnumber its fans, many of whom are eager to tell us what “wrong” with the WSL is. Apparently without thinking too much about this problem. Because the problem really isn’t that the WSL failed in its presentation of competitive professional surfing. It’s just that surfing has moved beyond ‘professional competitive surfing’.

Think back to 1976, the year the modern professional world tour was born. The two surf magazines, SURFER and SURFING were published every two months, that is, only six times a year. Surfing movies? Maybe two or three a year – and only if you lived in Huntington Beach. A big surf apparel company, Ocean Pacific, and a small Australian startup selling board shorts in the back of the car called Quiksilver. More importantly, a monocultural population of surfers made up almost entirely of young men, aged around 16 to 25, who tended to dress the same, ride the same types of surfboards, and dream the same dreams, most involving a trip to Hawaii – the North Shore, in particular, being portrayed in the media that existed as surfing Nirvana.

These guys certainly weren’t in the picture when contest surfing was in its infancy – and “freesurfing” wasn’t a thing. Photo: Jamie O’Brien//screen capture

The story of a handful of surfers, almost exclusively from Hawaii and Australia, making a marginal living by touring internationally, the big payoff being the winter season on the North Shore, was an easy sell. , and an even easier way to market t-shirts and board shorts. So, with nothing else going on in surfing at the time, except for the occasional discovery of an exotic new wave, impossible for most surfers to access, professional competitive surfing ignited the imagination of the aforementioned monoculture and flourished for some time; the only game in town, if you were to believe the surf media.

A game that in its intent and execution has changed very little over the past 46 years, except to reduce the number of annual events and increase the number of participating Brazilian surfers. Other than that, at its core, the pro tour format remains virtually indistinguishable from its earliest incarnation, poor judgment and uncooperative surf conditions included. But then consider how much the surfing world has changed in those same decades. Imagine, back when there were no Todos Santos, Maverick’s, Peahi, Mullaghmore, Nazare or Aussie slabs; no Tavarua, Gnaraloo, Mentawai Islands, Desert Point, Skeleton Bay, Salina Cruz or Boilers; no Surf Ranch or Waco Surf; No VCRs, DVDs, digital cameras, GoPros or drones; no surf forecasts, surf resorts or surf schools; no modern longboards, mid-lengths, soft-tops, “alternative” surfboards, SUPs or foils; Very few female surfers; no Kassia Meador, Kelia Moniz, Leah Dawson, Honolua Blomfield or Kelis Keliopa’a. No “freesurfers”, no Dave Rastovich, Mason Ho or Torren Martyn. No blogs or vlogs; no Nathan Florence at Pipe, Nic von Rupp in Europe or John John Florence sailing across the Pacific.

Over the years, while professional competitive surfing has always been touted as a big deal, surfing has obviously had other ideas. These ideas collectively manifested into the wonderfully diverse and widely enjoyed activity/lifestyle we know today. Who still has room for a professional competitive tour; that a handful of men and women are still making the rounds, pulling on and taking off soggy singlets between sleeves while complaining about judging, is, for a relatively small but passionate group of contest fans, an entertaining slice of our subculture. But only a slice. Seen in this light, the only thing the WSL gets wrong is its overstatement of the level of engagement of the wider surfing world. It’s pretty clear at this point that no matter how well the WSL works, the majority of the sport quite naturally grew and developed other interests – and in doing so left the professional circuit behind.

Comments are closed.